A temple for pigs? for swine? for hogs? Not a temple to worship them in, nor a temple for them to be sacrificed in. A temple for them to live in. These are not the pigs which invented their own form of latin, or those powerful Orwellian pigs, but normal pigs bred for slaughter. It is a shed-cum-temple for an animal closer to us in its genetic make-up than most. Perhaps a comedic thought at first, a classical temple to house livestock, the temple-shed requires a closer look; it is a challenge to our preconceptions about agriculture.

Advancements in cultivation and investment in land saw the creation of the ‘gentleman farmer’ in the mid-1700s. This social rise, combined with scale and lack of definitive architectural language, marked agricultural structures as the ideal place to express the status of these newly powerful farmers. They also provided a playground for experiments with style. Buildings for all manner of farm animals sparked the imagination of many designers and spawned a wealth of pattern books for agricultural structures.

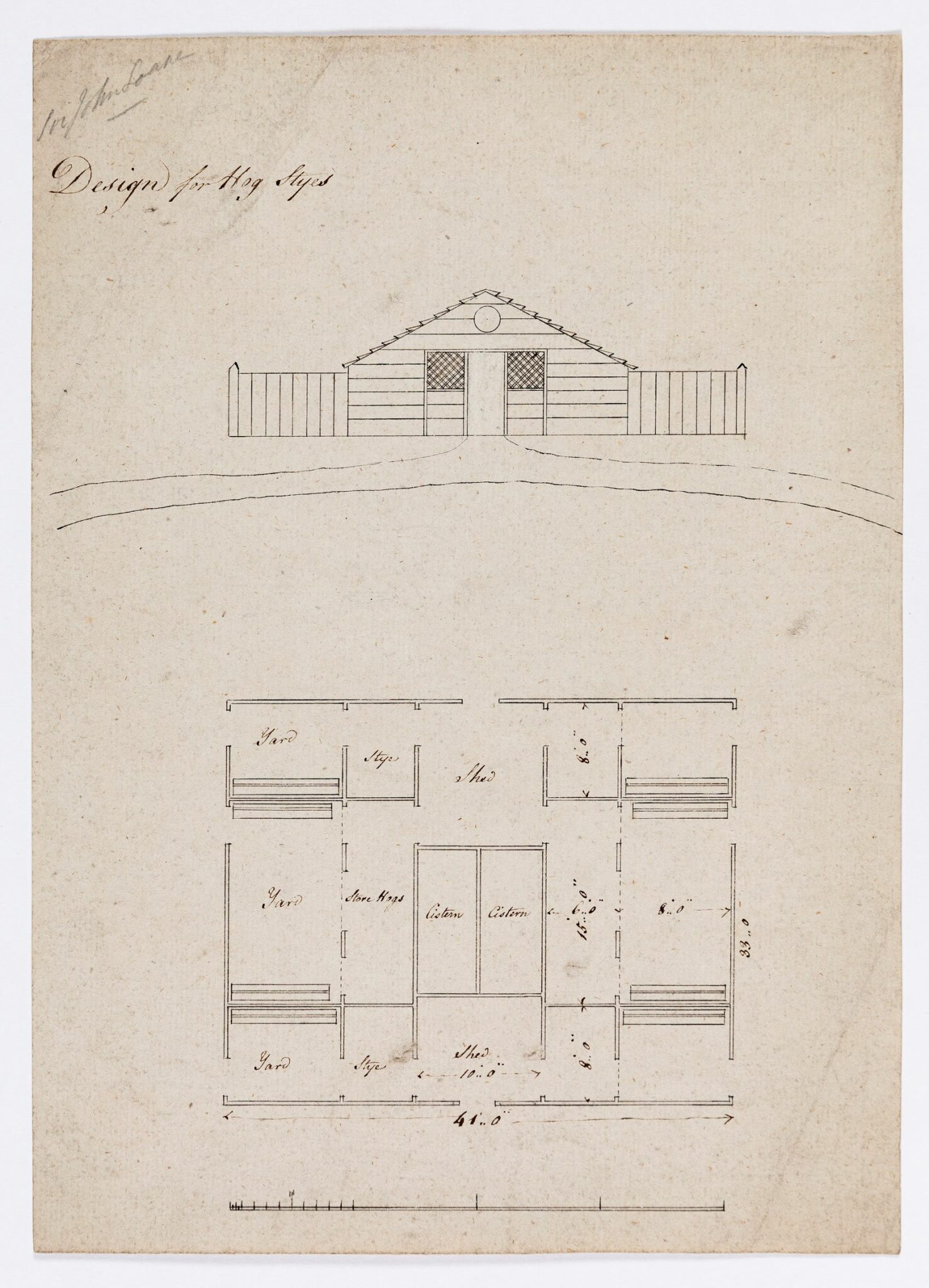

Sir John Soane’s design for a hog stye, as shown in a drawing now in the Drawing Matter collection, is a classically ordered and pedimented pig’s house, shown in plan and elevation. A simple line drawing outlines the shape and minimal features of its facade. Unlike our first thoughts of a classical temple, Soane’s appears small, on a human scale, set off a thin, winding footpath, unimposing and restrained. Lines placed horizontally on the main structure and vertically on its wings suggest an easily assembled material, a wooden cladding to create walls. The plan offers a defined set of pens, and walkways within a rectangular plot. On its facade is a central gabled roof with two large rectangular openings, and a centrally placed ‘Palladian’ circular window. The classical temple facade of the structure is flattened and unadorned: the pediment is reduced to a gable, the columns reduced to the wooden boarding and large doorways.

Soane’s classical references make an appropriate monument to a period of great agricultural prosperity. His allusions to a classical temple are not for the pigs but the owner – in this case presumably for Philip Yorke, the 1st Earl of Hardwick, for his development of Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire. Yet, while the idea of classicising the stye may be suited to status the farmer, its properties also offer the pigs a functional structure. Determined by the decorum of classicism, the temple-stye takes the form of the lowly Tuscan order, a primitive, stocky building with deep hanging eaves. An approach which suits the animal’s low stature, and need for shade. The symmetry, and structure of the classical orders offers division and control, Soane’s plan demonstrates the gridded interior of the pens; an ordered space for the animals to sleep and eat. This division equally worked on whole farm complexes, often created on a grid plan, with the pig sties at a far end (pig sties were often treated as separate units so that the smell from it would not affect the horses in their stables, as there is no animal that delights more in cleanliness than the horse). The drawing’s simplicity, its flat, reduced forms are an indication of this functionality.

This split between the needs of the owner and the animals is perhaps highlighted further in two other designs Soane made in 1780, for the Bishop of Derry. He produced two schemes for a dog house – a ‘residence for a canine family’ – a decorative one, for ‘ancient times’ and the other, which was less ornate, for ‘modern times’. The drawings for these take the same format as the hog stye, a plan below an elevation. The ‘ancient version’ was adorned with Doric columns and prancing hounds on the roof around the base of its dome. It is annotated with the inscription, ‘Elevation and Plan of a dog house, designed for a nobleman’, Soane’s highly ornate version, inspired by the temples at Paestum, embodies the status of the owner. Yet the description of both also highlights a ‘canal to run through each […] to keep the Apartments clean’. Therefore much like the hog stye, we see here the duality of the structure, where the classical lends itself well to the utilitarian features of a farm but equally the decorum of a ‘nobleman’.

Both Soane’s hog stye and dog house offer these dual functions through their drawings. At the top of the page, the elevation presents their classical form. The dog house, with its rounded arches and dome in a landscaped setting, the hog stye with a more subdued classical representation, where inferences of pediments and columns can be made from geometric forms. In plan we can again see the influence of the classical, through the placement of interior supports, and in their overall shapes. However, it also conveys the practicalities of the structure, the dog-temple’s waterways and the temple-stye’s pens.

So the temple-stye returns to my initial comic thoughts, losing some of its absurdity. It is classicism for the gentleman farmer and the pigs, working, on different levels, for both. The creative freedom enabled by social change, but equally these agricultural structures, is both explored and carefully considered by Soane.

Advancements in cultivation and investment in land saw the creation of the ‘gentleman farmer’ in the mid-1700s. This social rise, combined with scale and lack of definitive architectural language, marked agricultural structures as the ideal place to express the status of these newly powerful farmers. They also provided a playground for experiments with style. Buildings for all manner of farm animals sparked the imagination of many designers and spawned a wealth of pattern books for agricultural structures.

Sir John Soane’s design for a hog stye, as shown in a drawing now in the Drawing Matter collection, is a classically ordered and pedimented pig’s house, shown in plan and elevation. A simple line drawing outlines the shape and minimal features of its facade. Unlike our first thoughts of a classical temple, Soane’s appears small, on a human scale, set off a thin, winding footpath, unimposing and restrained. Lines placed horizontally on the main structure and vertically on its wings suggest an easily assembled material, a wooden cladding to create walls. The plan offers a defined set of pens, and walkways within a rectangular plot. On its facade is a central gabled roof with two large rectangular openings, and a centrally placed ‘Palladian’ circular window. The classical temple facade of the structure is flattened and unadorned: the pediment is reduced to a gable, the columns reduced to the wooden boarding and large doorways.

Soane’s classical references make an appropriate monument to a period of great agricultural prosperity. His allusions to a classical temple are not for the pigs but the owner – in this case presumably for Philip Yorke, the 1st Earl of Hardwick, for his development of Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire. Yet, while the idea of classicising the stye may be suited to status the farmer, its properties also offer the pigs a functional structure. Determined by the decorum of classicism, the temple-stye takes the form of the lowly Tuscan order, a primitive, stocky building with deep hanging eaves. An approach which suits the animal’s low stature, and need for shade. The symmetry, and structure of the classical orders offers division and control, Soane’s plan demonstrates the gridded interior of the pens; an ordered space for the animals to sleep and eat. This division equally worked on whole farm complexes, often created on a grid plan, with the pig sties at a far end (pig sties were often treated as separate units so that the smell from it would not affect the horses in their stables, as there is no animal that delights more in cleanliness than the horse). The drawing’s simplicity, its flat, reduced forms are an indication of this functionality.

This split between the needs of the owner and the animals is perhaps highlighted further in two other designs Soane made in 1780, for the Bishop of Derry. He produced two schemes for a dog house – a ‘residence for a canine family’ – a decorative one, for ‘ancient times’ and the other, which was less ornate, for ‘modern times’. The drawings for these take the same format as the hog stye, a plan below an elevation. The ‘ancient version’ was adorned with Doric columns and prancing hounds on the roof around the base of its dome. It is annotated with the inscription, ‘Elevation and Plan of a dog house, designed for a nobleman’, Soane’s highly ornate version, inspired by the temples at Paestum, embodies the status of the owner. Yet the description of both also highlights a ‘canal to run through each […] to keep the Apartments clean’. Therefore much like the hog stye, we see here the duality of the structure, where the classical lends itself well to the utilitarian features of a farm but equally the decorum of a ‘nobleman’.

Both Soane’s hog stye and dog house offer these dual functions through their drawings. At the top of the page, the elevation presents their classical form. The dog house, with its rounded arches and dome in a landscaped setting, the hog stye with a more subdued classical representation, where inferences of pediments and columns can be made from geometric forms. In plan we can again see the influence of the classical, through the placement of interior supports, and in their overall shapes. However, it also conveys the practicalities of the structure, the dog-temple’s waterways and the temple-stye’s pens.

So the temple-stye returns to my initial comic thoughts, losing some of its absurdity. It is classicism for the gentleman farmer and the pigs, working, on different levels, for both. The creative freedom enabled by social change, but equally these agricultural structures, is both explored and carefully considered by Soane.