Folly

Book Three

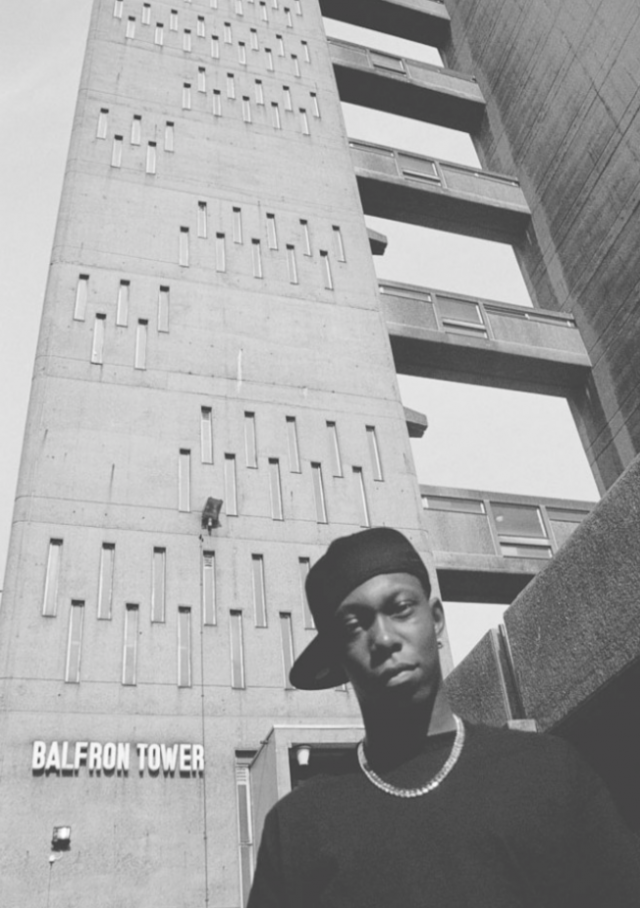

2. A Brand New Day: Urban Marginality, Social Housing and the Identity of Grime in Bow, East London

In 2003, Dylan Kwabena Mills won the revered Mercury Award for his debut album ‘Boy in Da Corner’. The 19-year old from Bow, East London was praised for his acute sensibility to the disintegration of his physical world and the visceral description of his area’s desperate social, economic and political landscape. Grime, the music genre that he championed, is a prosaic and unapologetic expression of its urban setting and in particular attributes a hyperlocal focus on Bow as the primary area where the genre developed.

The young artist, known more famously by his stage name ‘Dizzee Rascal’, collected the Mercury Award and returned back to his home on the Lincoln Estate, just south of Victoria Park. He struggled to comprehend the disjunction between the two worlds which he had just occupied, but always knew that the album ‘Boy in Da Corner’ was meant to be a prosaic documentation of his life and the depths from which he had come. In the opening bars of ‘Brand New Day’, the fourth track on his breakthrough album, Dizzee bemoans:

‘MCs better start chatting about what’s really happening, because if you ain’t

chatting about what’s happening, where you living? What you talking about?’

By the end of the decade, the work was regularly cited among some of the greatest albums of its generation, a visionary project that not only paved the way for a whole genre, but changed the conversation about the condition of East London’s social housing under the growing pressure of New Labour’s plans to regenerate much of inner city London.

Grime emerged in London’s East-End during the turn of the millennium. Developing from UK Garage but drawing influence from dancehall, ragga and hip-hop, the style is typified by rapid, syncopated breakbeats and an aggressive, anti-establishment sound. Specifically, the genre attributes a hyperlocal focus on Bow as the space where the music was born, alongside some of its most iconic individuals – Dizzee Rascal, Ruff Sqwad and Wiley – ‘The Godfather’. Connections to this area’s immediate context, social environment and sites of significance are entwined in a local system that form the foundation for this specific cultural production to occur.

Bow itself lies within a particular urban condition. The historic settlement of immigrants alongside the development of the inner city during the 1960s and 70s transgressed the frontier between core and periphery, creating immediate and intense encounters of ethno-racial relationships. This, in turn, influenced the sonic genealogy of the music, the particular cultural strands they drew from, and how the early Grime artists reflected on their position in the wider context of the city.

Whilst the census did not collect data on ethnicity until 1991, estimates throughout the post-war period indicate that by 1971 there were up to 500,000 West Indians living in the UK as its largest minority group. The period of formal decolonisation and post-war migrations of colonised peoples into British-based labour markets brought, as Stuart Hall describes, the ‘Other of the imperial Self back home.’ Urban space in Bow started to delineate itself along class and racial lines as the white working class who dominated the docks of East London became eager to separate themselves from the ‘the gregarious, noisy habits of the immigrants.’

As the white middle class in East London fled to the suburbs of Essex and Dagenham, they left the racially divided and contested inner city to poorer whites and people of colour. ‘Outer’ was projected as the locus of desire, the terminus of upward mobility, whilst ‘inner; was painted as a bleak, anarchic margin to be avoided. The A12 and A14, for instance, run North to South toward Blackwall Tunnel and effectively provide a six-lane motorway that carves eastern Bow in two, siphoning off the Aberfeldy Village in particular.

On a more intimate level, the scale of this infrastructure was felt as a purposeful barrier to contain communities within their local area, and prevent them from leaving their locality. Increased security barriers and a singular crossing point from Poplar DLR Station to One Canada Square made it clear that the former was not wanted or included in the new age development of the city. After all, the notion of peripheral space is relative: it does not require the absolute displacement of persons to or outside the literal margins of urban space, but merely their circumscription in terms of location and limitation of access – to power, to the realisation of rights, and to goods and services.

The progressive build-up of infrastructural severance and physical boundaries lead to the music adopting a marginalised identity and, in contextualising the music in this way, allows us to see London as a place where the informality of racial segregation and configuration of class boundaries are still being sustained, reproduced and amplified.

In 2003, when Dizzee Rascal released the track ‘Sittin’ Here’, he drew profound attention to the social malaise of a marginalised community. He had not only described its physical detritus, but also bleakly explored the damaging psyche of a young black male living in the immediacy of Bow’s council estates.

‘I’m just sitting here, I ain’t saying much I just think / my eyes don’t move left or

right, they just blink…

‘Cos it’s the same old story, shutters, runners, cats and money stacks… it’s the same old story, window tints and gloves for finger prints.’

In consuming and reflecting the social detritus in front of him, Dizzee had no choice but to present the social malaise of his immediate environment as immutable and self-perpetuating. Lincoln and Crossways Estate, to the North of Bow – and also where he frequented much of his young adult time - were typified by their mass abandonment, shuttering ply, and broken windows in abandoned flats.

In many ways, Grime’s sonic character was grounded in the material qualities of these ruinous estates - their physical condition influenced the vibrations, cadences and raw sounds used in the genre’s production. Eskibeat’s cadence, pitch and rapid tempo combined to create a music which sounded undoubtedly ‘cold, dirty and urban’. This ‘cold’, ‘dirty’ sound was an allegory to the physical squalor and deteriorating social conditions of the estates where the artists lived, enriched by producers who sampled snippets of police sirens, gunshots, or clanking metal from their local area.

Dizzee’s hypeman and childhood bestfriend, Aaron Williams, reinforces this, describing at times how primal the influence of their deteriorating surrounding environment was.

‘Sometimes we would just bang on the wall, and someone would freestyle over it. The hollowness of the wall provided the bass, the echo of the uninsulated stairwell would provide the reverb.

Then, it was the sounds of lifts at Mallard Point, the clank of a metal element falling from the ceiling, shattering glass in the Darkies – we absorbed and used them all.’

Yet, to reduce both the physical situation of Bow, and the latent Grime artists within it, to a simple condition of marginality would be to miss their inventiveness and the signs of emergent articulations that take them beyond the entrapments of a marginal space.

Bow’s young Grime artists were resilient and rebellious. First, there were the Pirates, who were ‘architects’ of the streets – stripping, re-wiring and re-configuring disused council flats to beam their new, illegal sound across the city.

‘Often,’ Aaron recalls, ‘You were in the kitchen spitting bars, and the transmitter was wired through to the next room, the aerial taped to the balcony and connected to the roof.’

In the case of Rinse FM’s first studio in an abandoned flat on the 8th floor of Mallard Point, early station DJs put up rigs in the lift shafts of the blocks, climbing to the top of the lift, then D-locking it, so the radio equipment was hanging from the motor that holds the lift in place. Through reconfiguring the existing service system of the tower block in this way, the artists created a new form of infrastructure within the building, bouncing radio signals from aerial to aerial, flat to flat.

Then, there were the journeymen. Grime formulated a complex geography within Bow that the artists navigated according to a finely tuned series of movements, assumptions and connections. The genre’s dispersal across several different spaces within Bow and East London meant that the artists’ had to formulate their own social and physical systems to connect these pockets of space together.

‘I would have never left my borough if it weren’t for Grime’, Ruffsqwad founder Shifty MC comments. ‘It allowed me to venture out of my home, because that’s where the events, the pirate radio, or the studio were. It allowed me to meet new people, create an understanding, transcend all that gang bullshit.’

Aaron and Shifty both recall an instance where they respectively travelled to London Fields, in nearby Dalston, to play for Roll Mission FM. The journey itself was unheard of, but is evidentiary of the connecting nature of Grime, which allowed both individuals to traverse the physical and social boundaries which kept Dalston and Bow separate. Similar journeys to Hackney Downs, or old industrial sites in Bethnal Green were a matter of risk for the individuals involved, ‘where we wouldn’t know if those ends were safe, or would be welcoming to us – they weren’t our patch, but we had to go.’

Here, Grime acted as the over-arching force to provide a platform for opposing groups of young artists in Bow to travel through respective ‘ends’ or ‘areas’ of ownership, as well as to establish conflicting but proximate territories. The coupling of these trajectories produces an intricate patchwork of zones of relative security which artists in the area negotiate, recognise and pass through.

The very least that this music and its associated spatiality can offer us today, as Paul Gilroy argues, is ‘an analogy for comprehending the lines of affiliation and association which take the idea of the diaspora beyond its symbolic status as the fragmentary opposite of an imputed racial essence.’ Indeed, Grime not only spoke from this diasporic voice, but ingrained itself in the physical fabric of the city – marking itself as a valuable proponent in Bow’s inner city systems, and as a powerful force which alleviated communities disenfranchised by urban life.

Indeed, the emphasis that Grime in Bow placed on community, collaboration and connection among residents seemingly immiserated by urban life can be seen as ‘infrastructure’ to provide a platform for and to reproduce life in the city. Its power ultimately came from transmuting the pain and pleasure of inner-city life into music for the voiceless, the immiserated, the marginalised. To divorce this cultural expression from its immediate urban environment is to grossly misunderstand the genre and the area it comes from.

As such, I argue that Grime during the early 2000s was more than just a cultural expression, but an active proponent in the fabric of the city, altering its physical space as well as its social boundaries for the lives of those in Bow who engaged with it.

Nabil Haque

The young artist, known more famously by his stage name ‘Dizzee Rascal’, collected the Mercury Award and returned back to his home on the Lincoln Estate, just south of Victoria Park. He struggled to comprehend the disjunction between the two worlds which he had just occupied, but always knew that the album ‘Boy in Da Corner’ was meant to be a prosaic documentation of his life and the depths from which he had come. In the opening bars of ‘Brand New Day’, the fourth track on his breakthrough album, Dizzee bemoans:

‘MCs better start chatting about what’s really happening, because if you ain’t

chatting about what’s happening, where you living? What you talking about?’

By the end of the decade, the work was regularly cited among some of the greatest albums of its generation, a visionary project that not only paved the way for a whole genre, but changed the conversation about the condition of East London’s social housing under the growing pressure of New Labour’s plans to regenerate much of inner city London.

Grime emerged in London’s East-End during the turn of the millennium. Developing from UK Garage but drawing influence from dancehall, ragga and hip-hop, the style is typified by rapid, syncopated breakbeats and an aggressive, anti-establishment sound. Specifically, the genre attributes a hyperlocal focus on Bow as the space where the music was born, alongside some of its most iconic individuals – Dizzee Rascal, Ruff Sqwad and Wiley – ‘The Godfather’. Connections to this area’s immediate context, social environment and sites of significance are entwined in a local system that form the foundation for this specific cultural production to occur.

Bow itself lies within a particular urban condition. The historic settlement of immigrants alongside the development of the inner city during the 1960s and 70s transgressed the frontier between core and periphery, creating immediate and intense encounters of ethno-racial relationships. This, in turn, influenced the sonic genealogy of the music, the particular cultural strands they drew from, and how the early Grime artists reflected on their position in the wider context of the city.

Whilst the census did not collect data on ethnicity until 1991, estimates throughout the post-war period indicate that by 1971 there were up to 500,000 West Indians living in the UK as its largest minority group. The period of formal decolonisation and post-war migrations of colonised peoples into British-based labour markets brought, as Stuart Hall describes, the ‘Other of the imperial Self back home.’ Urban space in Bow started to delineate itself along class and racial lines as the white working class who dominated the docks of East London became eager to separate themselves from the ‘the gregarious, noisy habits of the immigrants.’

As the white middle class in East London fled to the suburbs of Essex and Dagenham, they left the racially divided and contested inner city to poorer whites and people of colour. ‘Outer’ was projected as the locus of desire, the terminus of upward mobility, whilst ‘inner; was painted as a bleak, anarchic margin to be avoided. The A12 and A14, for instance, run North to South toward Blackwall Tunnel and effectively provide a six-lane motorway that carves eastern Bow in two, siphoning off the Aberfeldy Village in particular.

On a more intimate level, the scale of this infrastructure was felt as a purposeful barrier to contain communities within their local area, and prevent them from leaving their locality. Increased security barriers and a singular crossing point from Poplar DLR Station to One Canada Square made it clear that the former was not wanted or included in the new age development of the city. After all, the notion of peripheral space is relative: it does not require the absolute displacement of persons to or outside the literal margins of urban space, but merely their circumscription in terms of location and limitation of access – to power, to the realisation of rights, and to goods and services.

The progressive build-up of infrastructural severance and physical boundaries lead to the music adopting a marginalised identity and, in contextualising the music in this way, allows us to see London as a place where the informality of racial segregation and configuration of class boundaries are still being sustained, reproduced and amplified.

In 2003, when Dizzee Rascal released the track ‘Sittin’ Here’, he drew profound attention to the social malaise of a marginalised community. He had not only described its physical detritus, but also bleakly explored the damaging psyche of a young black male living in the immediacy of Bow’s council estates.

‘I’m just sitting here, I ain’t saying much I just think / my eyes don’t move left or

right, they just blink…

‘Cos it’s the same old story, shutters, runners, cats and money stacks… it’s the same old story, window tints and gloves for finger prints.’

In consuming and reflecting the social detritus in front of him, Dizzee had no choice but to present the social malaise of his immediate environment as immutable and self-perpetuating. Lincoln and Crossways Estate, to the North of Bow – and also where he frequented much of his young adult time - were typified by their mass abandonment, shuttering ply, and broken windows in abandoned flats.

In many ways, Grime’s sonic character was grounded in the material qualities of these ruinous estates - their physical condition influenced the vibrations, cadences and raw sounds used in the genre’s production. Eskibeat’s cadence, pitch and rapid tempo combined to create a music which sounded undoubtedly ‘cold, dirty and urban’. This ‘cold’, ‘dirty’ sound was an allegory to the physical squalor and deteriorating social conditions of the estates where the artists lived, enriched by producers who sampled snippets of police sirens, gunshots, or clanking metal from their local area.

Dizzee’s hypeman and childhood bestfriend, Aaron Williams, reinforces this, describing at times how primal the influence of their deteriorating surrounding environment was.

‘Sometimes we would just bang on the wall, and someone would freestyle over it. The hollowness of the wall provided the bass, the echo of the uninsulated stairwell would provide the reverb.

Then, it was the sounds of lifts at Mallard Point, the clank of a metal element falling from the ceiling, shattering glass in the Darkies – we absorbed and used them all.’

Yet, to reduce both the physical situation of Bow, and the latent Grime artists within it, to a simple condition of marginality would be to miss their inventiveness and the signs of emergent articulations that take them beyond the entrapments of a marginal space.

Bow’s young Grime artists were resilient and rebellious. First, there were the Pirates, who were ‘architects’ of the streets – stripping, re-wiring and re-configuring disused council flats to beam their new, illegal sound across the city.

‘Often,’ Aaron recalls, ‘You were in the kitchen spitting bars, and the transmitter was wired through to the next room, the aerial taped to the balcony and connected to the roof.’

In the case of Rinse FM’s first studio in an abandoned flat on the 8th floor of Mallard Point, early station DJs put up rigs in the lift shafts of the blocks, climbing to the top of the lift, then D-locking it, so the radio equipment was hanging from the motor that holds the lift in place. Through reconfiguring the existing service system of the tower block in this way, the artists created a new form of infrastructure within the building, bouncing radio signals from aerial to aerial, flat to flat.

Then, there were the journeymen. Grime formulated a complex geography within Bow that the artists navigated according to a finely tuned series of movements, assumptions and connections. The genre’s dispersal across several different spaces within Bow and East London meant that the artists’ had to formulate their own social and physical systems to connect these pockets of space together.

‘I would have never left my borough if it weren’t for Grime’, Ruffsqwad founder Shifty MC comments. ‘It allowed me to venture out of my home, because that’s where the events, the pirate radio, or the studio were. It allowed me to meet new people, create an understanding, transcend all that gang bullshit.’

Aaron and Shifty both recall an instance where they respectively travelled to London Fields, in nearby Dalston, to play for Roll Mission FM. The journey itself was unheard of, but is evidentiary of the connecting nature of Grime, which allowed both individuals to traverse the physical and social boundaries which kept Dalston and Bow separate. Similar journeys to Hackney Downs, or old industrial sites in Bethnal Green were a matter of risk for the individuals involved, ‘where we wouldn’t know if those ends were safe, or would be welcoming to us – they weren’t our patch, but we had to go.’

Here, Grime acted as the over-arching force to provide a platform for opposing groups of young artists in Bow to travel through respective ‘ends’ or ‘areas’ of ownership, as well as to establish conflicting but proximate territories. The coupling of these trajectories produces an intricate patchwork of zones of relative security which artists in the area negotiate, recognise and pass through.

The very least that this music and its associated spatiality can offer us today, as Paul Gilroy argues, is ‘an analogy for comprehending the lines of affiliation and association which take the idea of the diaspora beyond its symbolic status as the fragmentary opposite of an imputed racial essence.’ Indeed, Grime not only spoke from this diasporic voice, but ingrained itself in the physical fabric of the city – marking itself as a valuable proponent in Bow’s inner city systems, and as a powerful force which alleviated communities disenfranchised by urban life.

Indeed, the emphasis that Grime in Bow placed on community, collaboration and connection among residents seemingly immiserated by urban life can be seen as ‘infrastructure’ to provide a platform for and to reproduce life in the city. Its power ultimately came from transmuting the pain and pleasure of inner-city life into music for the voiceless, the immiserated, the marginalised. To divorce this cultural expression from its immediate urban environment is to grossly misunderstand the genre and the area it comes from.

As such, I argue that Grime during the early 2000s was more than just a cultural expression, but an active proponent in the fabric of the city, altering its physical space as well as its social boundaries for the lives of those in Bow who engaged with it.

Nabil Haque